Siege Of Savannah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The siege of Savannah or the Second Battle of Savannah was an encounter of the

D'Estaing began landing troops below the city on September 12, and began moving in by September 16. Confident of victory, and believing that Maitland's reinforcements would be prevented from reaching Savannah by Lincoln, he offered Prevost the opportunity to surrender. Prevost delayed, asking for 24 hours of truce. Owing to miscommunication about who was responsible for preventing Maitland's movements, the waterways separating South Carolina's Hilton Head Island from the mainland were left unguarded, and Maitland was able to reach Savannah hours before the truce ended. Prevost's response to d'Estaing's offer was a polite refusal, despite the arrival of Lincoln's forces.

On 19 September, as

D'Estaing began landing troops below the city on September 12, and began moving in by September 16. Confident of victory, and believing that Maitland's reinforcements would be prevented from reaching Savannah by Lincoln, he offered Prevost the opportunity to surrender. Prevost delayed, asking for 24 hours of truce. Owing to miscommunication about who was responsible for preventing Maitland's movements, the waterways separating South Carolina's Hilton Head Island from the mainland were left unguarded, and Maitland was able to reach Savannah hours before the truce ended. Prevost's response to d'Estaing's offer was a polite refusal, despite the arrival of Lincoln's forces.

On 19 September, as

Against the advice of many of his officers, d'Estaing launched the assault against the British position on the morning of October 9. The success depended in part on the secrecy of some its aspects, which were betrayed to Prevost well before the operations were supposed to begin around 4:00 am. Fog caused troops attacking the Spring Hill redoubt to get lost in the swamps, and it was nearly daylight when the attack finally got underway. The redoubt on the right side of the British works had been chosen by the French admiral in part because he believed it to be defended only by militia. In fact, it was defended by a combination of militia and Scotsmen from John Maitland's 71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser's Highlanders, who had distinguished themselves at Stono Ferry. The militia included riflemen, who easily picked-off the white-clad French troops when the assault was underway. Admiral d'Estaing was twice wounded, and Polish

Against the advice of many of his officers, d'Estaing launched the assault against the British position on the morning of October 9. The success depended in part on the secrecy of some its aspects, which were betrayed to Prevost well before the operations were supposed to begin around 4:00 am. Fog caused troops attacking the Spring Hill redoubt to get lost in the swamps, and it was nearly daylight when the attack finally got underway. The redoubt on the right side of the British works had been chosen by the French admiral in part because he believed it to be defended only by militia. In fact, it was defended by a combination of militia and Scotsmen from John Maitland's 71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser's Highlanders, who had distinguished themselves at Stono Ferry. The militia included riflemen, who easily picked-off the white-clad French troops when the assault was underway. Admiral d'Estaing was twice wounded, and Polish

The battle is commemorated each year by

The battle is commemorated each year by

French free colored participation in the Battle of Savannah

Pictures of the "Chasseurs Volontaires" monument

by

Attack on British Lines

historical marker {{DEFAULTSORT:Siege Of Savannah 1779 in the United States 1779 in Georgia (U.S. state) Conflicts in 1779

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783) in 1779. The year before, the city of Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, had been captured by a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

expeditionary corps under Lieutenant-Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

Archibald Campbell Archibald Campbell may refer to:

Peerage

* Archibald Campbell of Lochawe (died before 1394), Scottish peer

* Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll (died 1513), Lord Chancellor of Scotland

* Archibald Campbell, 4th Earl of Argyll (c. 1507–1558) ...

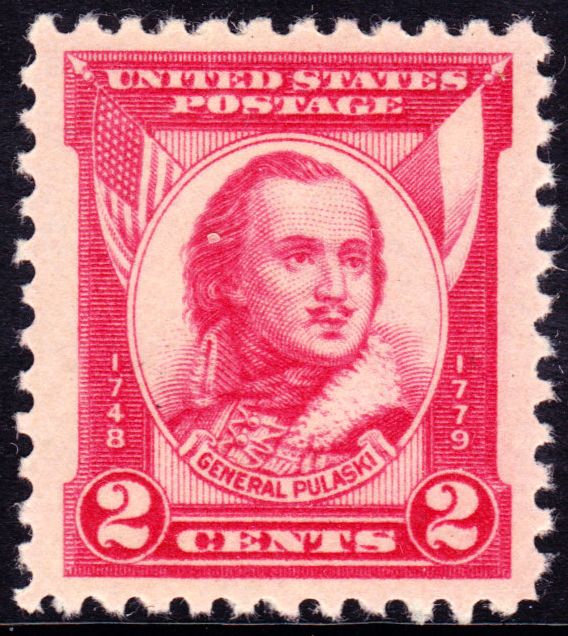

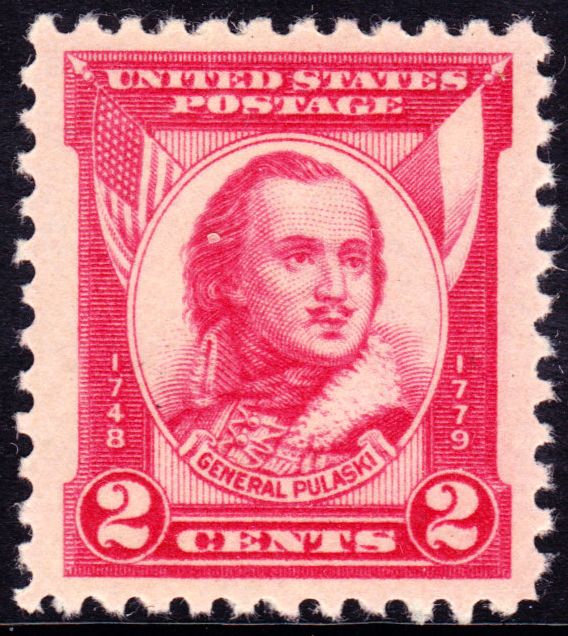

. The siege itself consisted of a joint Franco-American attempt to retake Savannah, from September 16 to October 18, 1779. On October 9 a major assault against the British siege works failed. During the attack, Polish nobleman Count Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski of the Ślepowron coat of arms (; ''Casimir Pulaski'' ; March 4 or March 6, 1745 Makarewicz, 1998 October 11, 1779) was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called, tog ...

, leading the combined cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

forces on the American side, was mortally wounded. With the failure of the joint attack, the siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

was abandoned, and the British remained in control of Savannah until July 1782, near the end of the war.

In 1779, more than 500 recruits from Saint-Domingue (the French colony which later became Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

), under the overall command of French nobleman Charles Hector, Comte d'Estaing

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, comte d'Estaing (24 November 1729 – 28 April 1794) was a French general and admiral. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of war of the ...

, fought alongside American colonial troops against the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

during the siege of Savannah. This was one of the most significant foreign contributions to the American Revolutionary War. This French-colonial force had been established six months earlier and was led by white officers. Recruits came from the black population and included free men of color as well as slaves seeking their freedom in exchange for their service.

Background

Following the failures of military campaigns in the northernUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

earlier in the American Revolutionary War, British military planners decided to embark on a southern strategy to conquer the rebellious colonies, with the support of Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

in the South. Their first step was to gain control of the southern ports of Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and Charleston, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. An expedition in December 1778 took Savannah with modest resistance from ineffective militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

defenses.

The Continental Army regrouped, and by June 1779 the combined army and militia forces guarding Charleston numbered between 5,000 and 7,000 men. General Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrenders ...

, commanding those forces, knew that he could not recapture Savannah without naval assistance; for this he turned to the French, who had entered the war as an American ally in 1778.

French Admiral the Comte d'Estaing

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, comte d'Estaing (24 November 1729 – 28 April 1794) was a French general and admiral. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of war of the ...

spent the first part of 1779 in the Caribbean, where his fleet and a British fleet monitored each other's movements. He took advantage of conditions to capture Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

in July before acceding to American requests for support in operations against Savannah. On September 3—an uncharacteristically early arrival as there was still substantial risk of seasonal hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

s—a few French ships arrived at Charleston with news that d'Estaing was sailing for Georgia with twenty-five ships of the line and 4,000 French troops. Lincoln and the French emissaries agreed on a plan of attack on Savannah, and Lincoln left Charleston with over 2,000 men on September 11.

Order of Battle

Allies

* Commanding General of Allied Forces,Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrenders ...

Continentals

* Artillery & Engineers, commanded byColonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

B. Beckman

** 4th South Carolina Regiment of Continental Artillery (1 coy)

* 1st Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Lachlan McIntosh

Lachlan McIntosh (March 17, 1725 – February 20, 1806) was a Scottish American military and political leader during the American Revolution and the early United States. In a 1777 duel, he fatally shot Button Gwinnett, a signer of the Declaratio ...

** 3rd South Carolina Regiment (Rangers) – Cavalry (2 sqns)

** 1st South Carolina Regiment – Infantry (1 small company)

** 6th South Carolina Regiment (Rifles) – Riflemen (roughly one small coy)

* 2nd Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Isaac Huger

** Huger's Continental Regiment (4 coys)

** Skirving's South Carolina Militia (2 coys)

** Harden's South Carolina Militia (1 coy)

** Garden's South Carolina Militia (1 coy)

* Georgia Militia Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Lachlan McIntosh

Lachlan McIntosh (March 17, 1725 – February 20, 1806) was a Scottish American military and political leader during the American Revolution and the early United States. In a 1777 duel, he fatally shot Button Gwinnett, a signer of the Declaratio ...

** Few's Georgia Militia (1 small coy)

** Dooley's Georgia Militia (1 coy)

** Twig's Georgia Militia (1 coy)

** Middleton's Georgia Militia (1 extremely reduced coy)

* Charleston Militia

** 2nd Militia Brigade commanded by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

M. Simmons (2 coys)

** Light Troops commanded by Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

J. Laurens (1 strengthened coy)

French

* Commanding Officer,Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Charles Henri Hector, Comte d'Estaing

The French expedition included detachments or full battalions from:

* Régiment de Champagne

* Régiment d'Auxerrois

* Régiment d'Agénois

* Régiment de Cambrésis

* Régiment de Hainaut (German)

* Régiment de Foix

* Régiment de Walsh (Irish)

* Régiment du Cap (colonial, Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

)

* Régiment de La Martinique (colonial, Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

)

* Régiment de La Guadeloupe (colonial, Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

)

* Régiment du Port–au–Prince (colonial, Saint-Domingue)

* Régiment de Metz (Artillery)

British

* Commanding Officer,Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Augustine Prévost

Major General Augustine Prévost (born Augustin Prévost) (b. 22 August 1723 Geneva, Republic of Geneva – d. 4 May 1786 East Barnet, England) was a Genevan-born British soldier who served in the Seven Years' War and the American War of Ind ...

* 16th Regiment of Foot

* 71st Regiment of Foot (Fraser's Highlanders)

* South Carolina Dragoons (Provincial)

* New York Volunteers

The New York Volunteers, also known as the New York Companies and 1st Dutchess County Company, was a British Loyalist Provincial regiment, which served with the British Army, during American Revolutionary War. Eventually, the New York Volunteer ...

* North Carolina Royalist Regiment (Provincial)

* 1 Battalion from De Lancey's Brigade

De Lancey's Brigade, also known as De Lancey's Volunteers, De Lancey's Corps, De Lancey's Provincial Corps, De Lancey's Refugees, and the "Cowboys" or "Cow-boys", was a Loyalist British provincial military unit, raised for service during the Ame ...

* King's Rangers (South Carolinan, Provincial)

* 2 German Regiments

* South Carolina Loyalist Militia

* Georgia Loyalist Militia

* Detachment of Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious light infantry and also one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy. The Corps of Royal Marine ...

* Detachment of Naval gunners serving in the naval battery

* Artillery

** 100 guns, howitzers, and mortars part of the Savannah Defences, including a naval battery

Defence

British defenses

British troop strength in the area consisted of about 6,500 regulars atBrunswick, Georgia

Brunswick () is a city in and the county seat of Glynn County in the U.S. state of Georgia. As the primary urban and economic center of the lower southeast portion of Georgia, it is the second-largest urban area on the Georgia coastline after Sa ...

, another 900 at Beaufort, South Carolina

Beaufort ( , a different pronunciation from that used by the city with the same name in North Carolina) is a city in and the county seat of Beaufort County, South Carolina, United States. Chartered in 1711, it is the second-oldest city in South ...

, under Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

John Maitland, and about 100 Loyalists at Sunbury, Georgia. General Augustine Prevost

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

, in command of these troops from his base at Savannah, was caught unprepared when the French fleet began to arrive off Tybee Island

Tybee Island is a city and a barrier island located in Chatham County, Georgia, 18 miles (29 km) east of Savannah, United States. Though the name "Tybee Island" is used for both the island and the city, geographically they are not identica ...

near Savannah and recalled the troops stationed at Beaufort and Sunbury to aid in the city's defense.

Captain Moncrief of the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

was tasked with constructing fortifications to repulse the invaders. Using 500–800 African-American slaves working up to twelve hours per day, Moncrief constructed an entrenched defensive line, which included redoubt

A redoubt (historically redout) is a fort or fort system usually consisting of an enclosed defensive emplacement outside a larger fort, usually relying on earthworks, although some are constructed of stone or brick. It is meant to protect soldi ...

s, nearly long, on the plains outside the city.

Vessels

The BritishRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

contributed two over-age frigates, and . They landed their guns and most of their men to reinforce the land forces. In addition, the British also deployed the armed brig and the armed ship , the latter from the East Florida navy. There were two galleys, and ''Thunder'', also from East Florida. Lastly, the British armed two merchant vessels, ''Savannah'' and ''Venus''.

Siege

D'Estaing began landing troops below the city on September 12, and began moving in by September 16. Confident of victory, and believing that Maitland's reinforcements would be prevented from reaching Savannah by Lincoln, he offered Prevost the opportunity to surrender. Prevost delayed, asking for 24 hours of truce. Owing to miscommunication about who was responsible for preventing Maitland's movements, the waterways separating South Carolina's Hilton Head Island from the mainland were left unguarded, and Maitland was able to reach Savannah hours before the truce ended. Prevost's response to d'Estaing's offer was a polite refusal, despite the arrival of Lincoln's forces.

On 19 September, as

D'Estaing began landing troops below the city on September 12, and began moving in by September 16. Confident of victory, and believing that Maitland's reinforcements would be prevented from reaching Savannah by Lincoln, he offered Prevost the opportunity to surrender. Prevost delayed, asking for 24 hours of truce. Owing to miscommunication about who was responsible for preventing Maitland's movements, the waterways separating South Carolina's Hilton Head Island from the mainland were left unguarded, and Maitland was able to reach Savannah hours before the truce ended. Prevost's response to d'Estaing's offer was a polite refusal, despite the arrival of Lincoln's forces.

On 19 September, as Charles-Marie de Trolong du Rumain

Chevalier Charles-Marie de Trolong du Rumain (30 September 1743 – 10 August 1780) was a French naval officer of the Ancien Régime.

Career

He took part in the War of American Independence, notably commanding the 10-gun cutter ''Curieuse'' ...

moved his squadron up the river, he exchanged fire with ''Comet'', ''Thunder'', ''Savannah'', and ''Venus''. The next day the British scuttled ''Rose'', which was leaking badly, just below the town to impede the French vessels from progressing further. They also burnt ''Savannah'' and ''Venus''. By scuttling ''Rose'' in a narrow part of the channel, the British effectively blocked it. Consequently, the French fleet was unable to assist the American assault.

''Germaine'' took up a position to protect the north side of Savannah's defenses. ''Comet'' and ''Thunder'' had the mission of opposing any attempt by the South Carolinian galleys to bombard the town. Over the next few days, British shore batteries assisted ''Comet'' and ''Thunder'' in engagements with the two South Carolinian galleys; during one of these, they severely damaged ''Revenge''.

The French commander, rejecting the idea of assaulting the British defenses, unloaded cannons from his ships and began a bombardment of the city. The city, rather than the entrenched defenses, bore the brunt of this bombardment, which lasted from October 3 to 8. "The appearance of the town afforded a melancholy prospect, for there was hardly a house that had not been shot through", wrote one British observer.Morrill, p. 60

When the bombardment failed to have the desired effect, d'Estaing changed his mind, and decided it was time to try an assault. He was motivated in part by the desire to finish the operation quickly, as scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

and dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

were becoming problems on his ships, and some of his supplies were running low. While a traditional siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

operation would likely have succeeded eventually, it would have taken longer than d'Estaing was prepared to stay.

Attack

Against the advice of many of his officers, d'Estaing launched the assault against the British position on the morning of October 9. The success depended in part on the secrecy of some its aspects, which were betrayed to Prevost well before the operations were supposed to begin around 4:00 am. Fog caused troops attacking the Spring Hill redoubt to get lost in the swamps, and it was nearly daylight when the attack finally got underway. The redoubt on the right side of the British works had been chosen by the French admiral in part because he believed it to be defended only by militia. In fact, it was defended by a combination of militia and Scotsmen from John Maitland's 71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser's Highlanders, who had distinguished themselves at Stono Ferry. The militia included riflemen, who easily picked-off the white-clad French troops when the assault was underway. Admiral d'Estaing was twice wounded, and Polish

Against the advice of many of his officers, d'Estaing launched the assault against the British position on the morning of October 9. The success depended in part on the secrecy of some its aspects, which were betrayed to Prevost well before the operations were supposed to begin around 4:00 am. Fog caused troops attacking the Spring Hill redoubt to get lost in the swamps, and it was nearly daylight when the attack finally got underway. The redoubt on the right side of the British works had been chosen by the French admiral in part because he believed it to be defended only by militia. In fact, it was defended by a combination of militia and Scotsmen from John Maitland's 71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser's Highlanders, who had distinguished themselves at Stono Ferry. The militia included riflemen, who easily picked-off the white-clad French troops when the assault was underway. Admiral d'Estaing was twice wounded, and Polish cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

officer Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski of the Ślepowron coat of arms (; ''Casimir Pulaski'' ; March 4 or March 6, 1745 Makarewicz, 1998 October 11, 1779) was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called, tog ...

, fighting with the Americans, was mortally wounded. By the time the second wave arrived near the redoubt, the first wave was in complete disarray, and the trenches below the redoubt were filled with bodies. Attacks intended as feint

Feint is a French term that entered English via the discipline of swordsmanship and fencing. Feints are maneuvers designed to distract or mislead, done by giving the impression that a certain maneuver will take place, while in fact another, or e ...

s against other redoubts of the British position were easily taken.

The second assault column was commanded by the Swedish Count Curt von Stedingk

Curt Bogislaus Ludvig Kristoffer von Stedingk (26 October 1746 – 7 January 1837) was a count of the von Stedingk family, and a successful Swedish army officer and diplomat who played a prominent role in Swedish foreign policy for several decade ...

, who managed to reach the last trench. He later wrote in his journal, "I had the pleasure of planting the American flag on the last trench, but the enemy renewed its attack and our people were annihilated by cross-fire". He was forced back by overwhelming numbers of British troops, left with some 20 men—all were wounded, including von Stedingk. He later wrote, "The moment of retreat with the cries of our dying comrades piercing my heart was the bitterest of my life".

After an hour of carnage, d'Estaing ordered a retreat. On October 17, Lincoln and d'Estaing abandoned the siege.

Aftermath and legacy

The battle was one of the bloodiest of the war. While Prevost claimed Franco-American losses at 1,000 to 1,200, the actual tally of 244 killed, nearly 600 wounded and 120 taken prisoner, was severe enough. British casualties were comparatively light: 40 killed, 63 wounded, and 52 missing. Sir Henry Clinton wrote, "I think that this is the greatest event that has happened the whole war," and celebratory cannons were fired when the news reached London.Morrill, p. 64 It was perhaps because of the siege's reputation as a famous British victory thatCharles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

chose the siege of Savannah as the place for Joe Willet to be wounded (losing his arm) in the novel Barnaby Rudge

''Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty'' (commonly known as ''Barnaby Rudge'') is a historical novel by British novelist Charles Dickens. ''Barnaby Rudge'' was one of two novels (the other was ''The Old Curiosity Shop'') that Dickens publ ...

.

Three currently-existing Army National Guard units (118th FA, 131st MP and 263rd ADA) are derived from American units that participated in the siege of Savannah. There are only thirty current U.S. Army units with lineages that go back to the colonial era.

Battlefield archaeology

In 2005, archaeologists with the Coastal Heritage Society (CHS) and the LAMAR Institute discovered portions of the British fortifications at Spring Hill, the site of the worst part of the Franco-American attack on October 9. The find represents the first tangible remains of the battlefield. In 2008, the CHS/LAMAR Institute archaeology team discovered another segment of the British fortifications in Madison Square. A detailed report of that project is available on line in pdf format from the CHS website. CHS archaeologists are currently finalizing a follow-up grant project in Savannah, which examined several outlying portions of the battlefield. These included the position of the Saint-Domingue reserve troops at the Jewish Burying Ground west of Savannah. An archaeology presentation and public meeting took place in February 2011 to gather suggestions for managing Savannah's Revolutionary War battlefield resources. Archaeologist Rita Elliott from the Coastal Heritage Society revealed Revolutionary War discoveries in Savannah stemming from the two "Savannah Under Fire" projects conducted from 2007 to 2011. The projects uncovered startling discoveries, including trenches, fortifications, and battle debris. The research also showed that residents and tourists are interested in these sites. Archaeologists described the findings and explored ways to generate economic income which could be used for improving the quality-of-life of area residents. The battle is commemorated each year by

The battle is commemorated each year by Presidential proclamation

A presidential proclamation is a statement issued by a US president on an issue of public policy and is a type of presidential directive.

Details

A presidential proclamation is an instrument that:

*states a condition,

*declares a law and require ...

, on General Pulaski Memorial Day

General Pulaski Memorial Day is a United States public holiday in honor of General Kazimierz Pułaski (spelled Casimir Pulaski in English), a Polish hero of the American Revolution. This holiday is held every year on October 11 by Presidential P ...

.

Influence on Haitian revolutionaries

The battle is much-remembered in Haitian history; theChasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue

Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue was a Dominican Creole regiment that was founded on 12 March 1779. Though the regiment was for non-whites, the officers were white, with the exception of Laurent François Lenoir, Marquis de Rouvray, who c ...

, consisting of some 545 ''gens de couleur

In ancient Rome, a gens ( or , ; plural: ''gentes'' ) was a family consisting of individuals who shared the same Roman naming conventions#Nomen, nomen and who claimed descent from a common ancestor. A branch of a gens was called a ''stirps'' (p ...

''— free men of color from Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

—fought with the Americans.

Henri Christophe

Henri Christophe (; 6 October 1767 – 8 October 1820) was a key leader in the Haitian Revolution and the only monarch of the Kingdom of Haiti.

Christophe was of Bambara ethnicity in West Africa, and perhaps of Igbo descent. Beginning with ...

, who later declared himself to be the king of (northern) Haiti, while a republic was established in southern Haiti, was 12-years old at the time and may have been among these troops.

Many other less-famous individuals from Saint-Domingue served in this regiment and formed the officer class of the rebel armies in the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

, especially in the northern province around today's Cap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien (; ht, Kap Ayisyen; "Haitian Cape"), typically spelled Cape Haitien in English and often locally referred to as or , is a commune of about 190,000 people on the north coast of Haiti and capital of the department of Nord. Previousl ...

, where the unit was recruited.

See also

* American Revolutionary War § War in the South. Places ' Siege of Savannah ' in overall sequence and strategic context. *Casimir Pulaski Monument in Savannah

The Casimir Pulaski Monument in Savannah, or Pulaski Monument on Monterey Square, is a 19th-century monument to Casimir Pulaski, in Monterey Square (Savannah, Georgia), Monterey Square, on Bull Street, Savannah, Georgia, not far from the battlefi ...

* William Jasper Monument

Notes

References

* Buker, George E. and Richard Apley Martin (July 1979) "Governor Tonyn's Brown-Water Navy: East Florida during the American Revolution, 1775-1778". ''Florida Historical Quarterly'', Vol. 58, No. 1, pp. 58–71. * * Marley, David. ''Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present''ABC-CLIO (1998). * *External links

French free colored participation in the Battle of Savannah

Pictures of the "Chasseurs Volontaires" monument

by

James Mastin

James Richard Mastin (1935–2016) was an American sculptor and painter, best known for his public monuments of life-sized bronze figures commemorating significant historical events and individuals. The hallmark of his work was meticulous craftsm ...

, located in Franklin Square, Savannah, Georgia

*

Attack on British Lines

historical marker {{DEFAULTSORT:Siege Of Savannah 1779 in the United States 1779 in Georgia (U.S. state) Conflicts in 1779

Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

History of Haiti

History of Savannah, Georgia

Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...